Zhou Daguan – A Record of Cambodia – NZJAS Review by Stephen McDowall

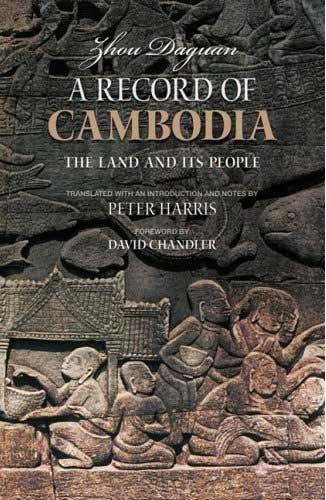

BOOK REVIEW: Zhou Daguan, A Record of Cambodia: The Land and its People. Translated with an introduction and notes by Peter Harris, and a foreword by David Chandler, Chiang Mai, Silkworm Books, 2007, xv + 150 pp. ISBN: 978-974-9511-24-4 (pbk.).

In the second month of the bingshen 丙申 year of the Yuanzhen 元貞 reign of the Yuan 元 dynasty [1296], a Chinese delegation representing the recently-crowned emperor Temür 鐵穆耳 (Chengzong 成宗; r. 1294-1307) set sail from the southern coastal city of Mingzhou 明州, headed for Cambodia.

We cannot be entirely sure of the delegation’s objective, nor of the role that was expected to be played by a young member of the mission named Zhou Daguan 周達觀.

What we do know is that Zhou’s account, written some time after the eleven months he spent in the capital Yasodharapura (now known as Angkor Thom) in 1296-97 and titled Zhenla fengtu ji 真臘風土記 [Account of the Customs and Geography of Cambodia], is the only surviving eyewitness account of the civilisation of Angkor. The work then, offers a unique glimpse of that world at the end of the thirteenth century, just as its golden age was beginning to draw to a close.

Given the importance of Zhou’s account, it seems astonishing that this slim volume, A Record of Cambodia: The Land and its People, translated with an introduction and copious notes by Peter Harris, represents the first ever translation of the work into English directly from the classical Chinese, but this is indeed the case.

Previous English renditions (the latest reprint of which appeared in 2007) have been based solely on Paul Pelliot’s (1878-1945) masterful French version of the work, Mémoires sur les Coutumes du Cambodge of 1902, and inevitably suffer from being too far removed from the original text. Peter Harris, by contrast, is able to draw not only on Pelliot’s pioneering study (and revised version with incomplete notes, posthumously published in 1951), but also on the ground-breaking scholarship of Xia Nai 夏鼐, whose annotated edition of Zhou’s text, Zhenla fengtu ji jiaozhu 真臘風土記校注 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2000) includes variants from thirteen editions. There is also a tremendous amount of new linguistic material in the present edition, with Harris making use of important studies by Michael Vickery, Bernhard Karlgren, Edwin G. Pulleyblank and others.

The impeccable scholarship of this study, combined with the accuracy of Harris’ fluent translation, make this version certain now to supersede that of Pelliot as the standard edition of Zhou’s account in any Western language.

The Record of Cambodia as it exists today is divided into 40 sections, but Harris notes that the present order suggests that they may at some point have been rearranged (17). Indeed, parts of the text ‘show clear signs of having been cut or mutilated’ (28), and Harris cites the seventeenth-century bibliophile Qian Zeng 錢曾 (1629–1700?), who claimed that the text on which presently-existing editions are based was ‘muddled and jumbled up, six or seven tenths of it missing, barely constituting a book at all’ (29).

As it stands it contains quite thorough descriptions of the architecture and customs at court, interesting details concerning such matters as sumptuary restrictions on dress, and more cursory observations on law, death, agriculture, sex, prostitution, slaves, language, trade, flora, animals, liquor, transport and various other topics. Harris renders Zhou’s text into accurate but free-flowing English, occasionally altering the sense of a word (the translation of the term fan 番 as ‘local’ is one example Harris himself signposts, 31-2), but always acknowledging where this has been done.

Of Zhou Daguan himself we know almost nothing, other than that he was a native of Wenzhou 溫州, but one of the strengths of this book is Harris’ skilful evocation of the ‘kind of frontier spirit’ (5) that existed in thirteenth-century Wenzhou and the other coastal cities that helped to connect southeast China to Asia and the wider world.

These were the ports from which large quantities of raw and manufactured goods, including lacquer, celadon, ceramics, silks, cinnabar, paper, musk, pewter and glass departed daily, and the people with whom Zhou grew up, we are told, were ‘traders, merchants and sailors, broad-minded, outward-looking [and] well-versed in the affairs of the world…’ (10).

As historians increasingly seek to highlight the roles of Asian societies in the early modern world economy, and become ever more aware of the ways in which the emerging discipline of global history can enhance our understanding of early modern cultures, the publication of this new edition of Zhou Daguan’s account of Cambodia seems extremely timely. Indeed, the Yasodharapura Zhou describes is a key site of global interaction, with immigrant Siamese who, unlike the locals, engage in silk production and are competent tailors (76), geese recently introduced from China (73), and a range of Chinese goods available for sale, including paper, combs, needles, mats and much more (71). Intriguingly, Zhou also tells us that ‘although cloth is woven domestically, it also comes from Siam and Champa. Cloth from the Western Seas 西洋 is often regarded as the best because it is so well-made and refined” (50). *

If we know little about its author, then we know even less about the publication history of the Zhenla fengtu ji itself, save that the book must have been circulating in some form by at least 1312, as it is referred to in Wu Qiuyan’s 吾邱衍 Zhusushan fang ji 竹素山房集, published in that year (41 n.17).

Zhou’s account was eventually included in the monumental Siku quanshu 四庫全書 collection initiated by the Qianlong 乾隆 emperor (Gaozong 高宗; r. 1736-96) in 1772, but the fact remains that no official record of the mission to Cambodia exists in any of the traditional Chinese sources. That omission links Zhou (and Harris) to another traveller of the Yuan era, Marco Polo, whose A Description of the World, a far lengthier but also far more problematic source of the history of the Yuan world, was revised and edited by Harris in a new edition published in 2008. **

In contrast to Polo, Harris notes, Zhou Daguan ‘gives us the impression he can be relied upon’ (2), and ‘seems to be scrupulous about indicating whether he is reporting something first- or second-hand’ (23). This is particularly evident in the section entitled ‘The Three Doctrines,’ in which Zhou describes details such as dress, but admits ignorance in other respects (‘I don’t know what the source of their beliefs is, 53).

The period during which Zhou visited Cambodia at the very end of the thirteenth century marks something of a turning point in the history of Angkor civilisation. It would be over a century before Yasodharapura was finally sacked by Siamese troops and the capital moved to the south of the country, but it is clear from what little we know that the massive construction projects that characterised the reigns of Angkor’s thirteenth-century rulers were missing from the following century (14-17). Zhou notes at one point that ‘as a result of repeated wars with the Siamese the land [surrounding the capital] has been completely laid to waste’ (79), an offhand remark that reads quite portentously to those of us who know how the story ends.

Harris notes that scholars such as Michael Vickery warn against assigning too much authority to Chinese and Sanskrit sources when assessing Angkor civilisation, and he judiciously draws attention to Zhou’s natural prejudices and assumptions (27). One obvious deficiency in the text (apart from its incompleteness) is that not a single Cambodian is referred to by name, and we simply know far too little about the publication history of the account to be able to speculate as to whether these were subsequently removed, or indeed, ever there at all.

But I would argue that – and as an historian of China I am quite prepared to declare my bias here – while the book provides just a glimpse of late-thirteenth century Angkor, it can tell us quite a lot more about China under Yuan rule, a period that as it stands is not particularly well served in terms of traditional source material. The fact that the people of Cambodia do not know how to make soy sauce (75) is probably of very little interest to an historian of Angkor, but the fact that a young Chinese deemed this worthy of note does at least tell us something, however trivial, about culinary practice under the Yuan.

More usefully perhaps, the observations Zhou makes regarding interregional trade, or his advice that ‘when a Chinese goes to this country, the first thing he must do is take in a woman, partly with a view to profiting from her trading abilities’ (70), can contribute much to our understanding of Chinese migration history.

Now brought back to life in Peter Harris’ outstanding new English edition, Zhou’s Record of Cambodia will no doubt find its way into the hands of a new generation of historians and anthropologists, but it should also appeal more generally to anyone interested in a fascinating civilisation about which we know so little.

* ‘Cloth from the Western Seas’ 西洋 is probably a reference to buckram from India, althoughit may also have come from somewhere on the Malaysian peninsular. Some commentators prefer to read the 布 here as 絲布 (i.e. silk). See Xia ed., Zhenla fengtu ji jiaozhu, pp. 87-88.

** The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008). This new edition was recently reviewed in the pages of this journal by Duncan Campbell.

© Copyright 2010New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies (NZJAS). This review originally appeared in the NZJAS journal and is reprinted here with the kind permission of the editor.

About the Reviewer

Dr. Stephen McDowall, is a Research Fellow in the Department of History at the University of Warwick.

His research interests include late-imperial Chinese history and literature, the literature of travel, China in the Western imagination, early modern global connections and Ming material & visual culture. His new book, Qian Qianyi’s Reflections on Yellow Mountain: Traces of a Late-Ming Hatchet and Chisel (Hong Kong University Press, 2009), examines the fascinating and complex world of late-Ming literati through an analysis of the youji 游記 [travel account] genre.