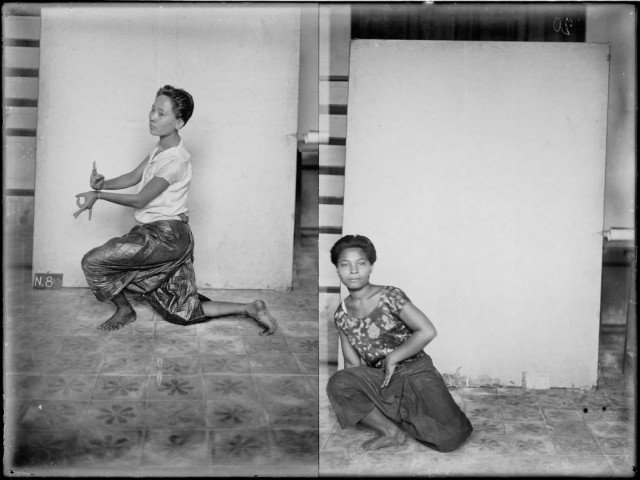

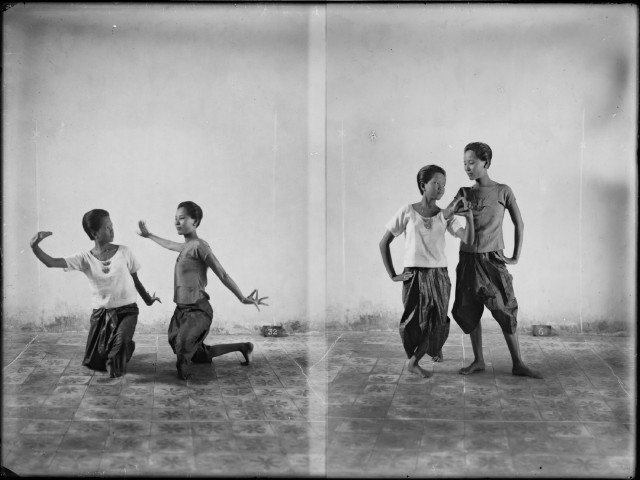

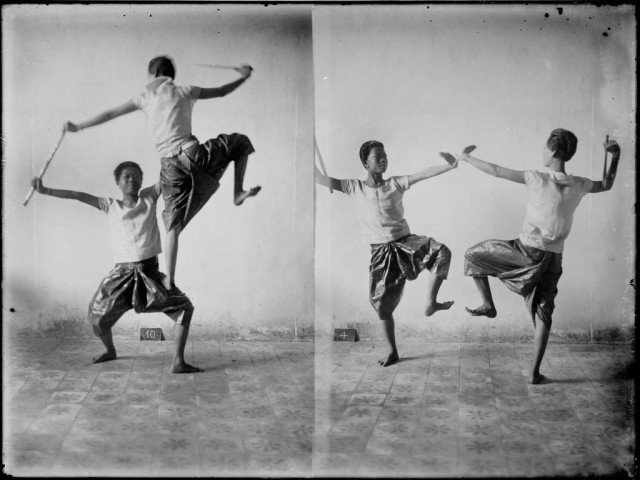

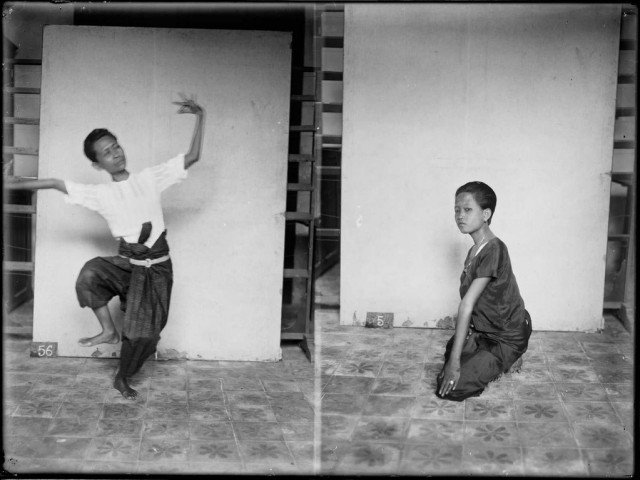

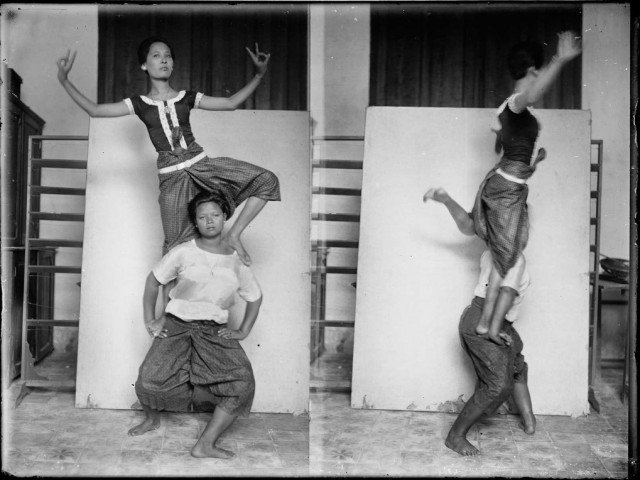

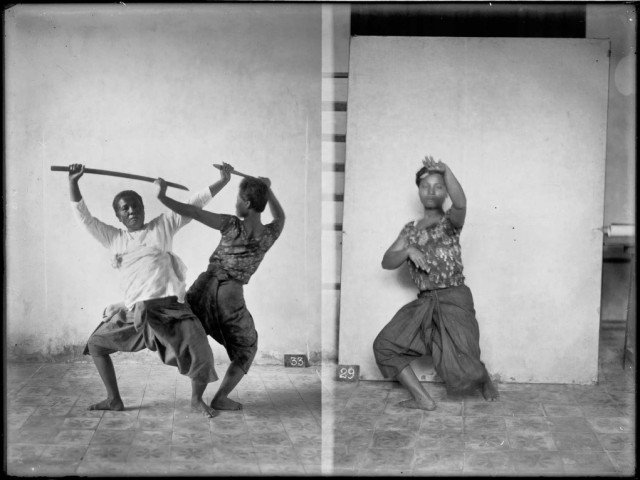

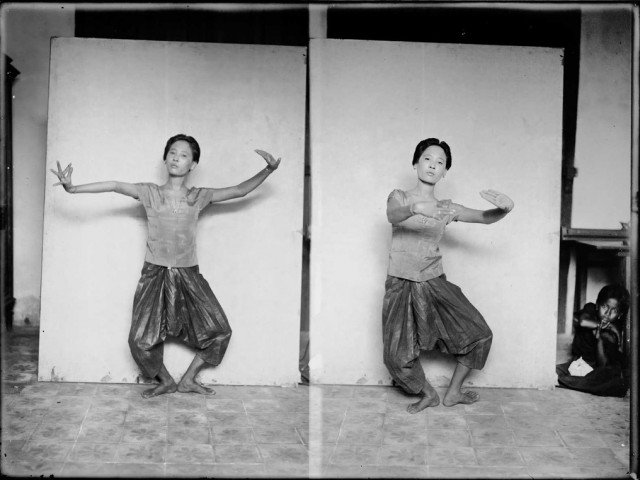

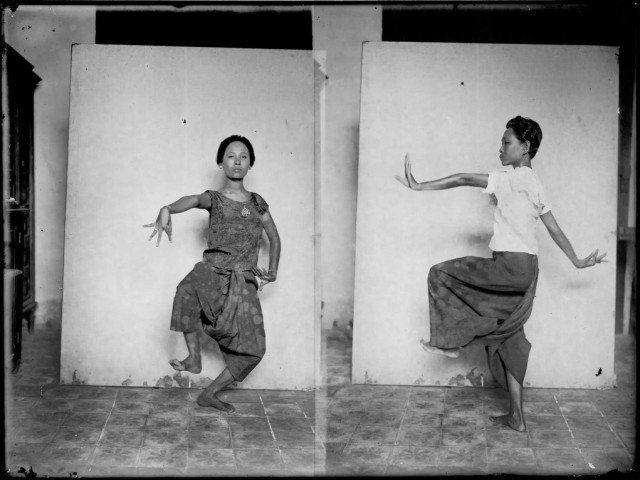

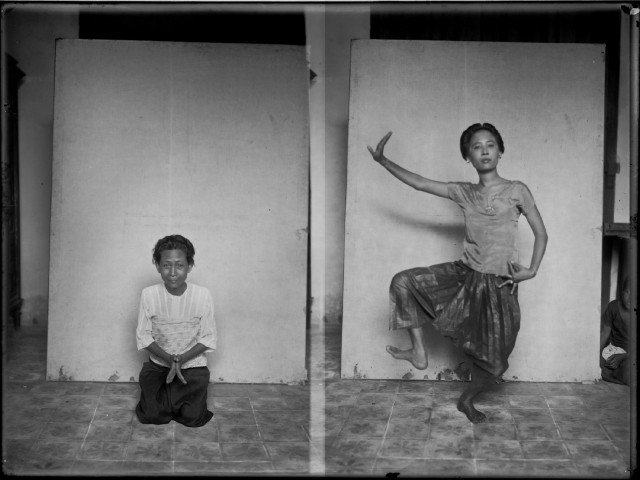

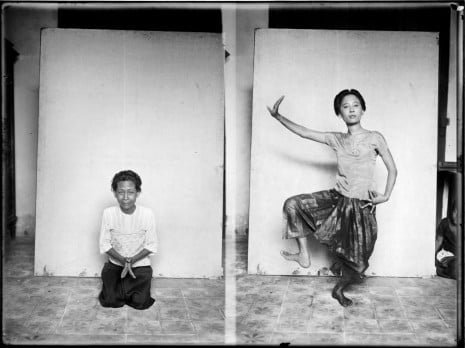

Royal Cambodian Dancers of Sisowath in 1927 Photos by George Groslier

This Cambodia Daily article by Michelle Vachon describes the Royal Cambodian dancers of Sisowath in 1927 photos by George Groslier. It originally appeared on April 1, 2013 as “Exhibition of Khmer Classical Dance Photos Opens in New York” and is reproduced here with permission from the copyright holder. The slide show features additional images from the Groslier collection, maintained by the National Museum of Cambodia.

“Cambodian royal dances, the admirable artistic tradition and all the indigenous past they represent are seriously threatened due to the very evolution of Cambodia and Western progress.”

George Groslier

These prophetic words could have been written at any time, but they were actually penned in 1928 by Georges Groslier, founder and director of the National Museum in Phnom Penh.

Georges Groslier’s concern for the future of Khmer classical dance had led him, one year earlier, to immortalize those dance movements in hundreds of photographs.

The images he took 86 years ago went on display Thursday at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, one of New York City’s most famed theaters. The exhibition, organized by the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, is part of the Season of Cambodia festival, which begins in two weeks in New York.

Phloeun Prim, director of the Phnom Penh-based Cambodian Living Arts, who originated the idea for Season of Cambodia, said Georges Groslier’s photographs were a perfect backdrop for the Cambodian Royal Ballet’s performance during the festival.

“Since Cambodia’s Royal Ballet would perform in New York [in May], I found them [the photographs] ideal to help the New York audience grasp the background of the country’s artistic history,” Mr. Prim said on Wednesday from New York.

In the early 20th century, Khmer classical dancers were part of the Royal Household. At the death of King Norodom in 1904, the number of dancers had drastically decreased due to King Sisowath’s reduced palace budget. By 1927, King Sisowath was 87 years old and Georges Groslier feared that the Royal Ballet would all but disappear when the King passed away. So, after obtaining the support of the Royal Palace, he started photographing classical dance for posterity.

George Groslier’s photo sessions took place at the National Museum in Phnom Penh and lasted months as every dancer’s movement had to be discussed and checked by master dancers before being photographed.

The result was 900 photos taken on glass negatives that laid forgotten until Bertrand Porte of the French research institution Ecole francaise d’Extreme-Orient (EFEO) and his colleagues in the museum’s restoration workshop found them neglected in the museum and rescued them in the late 2000s. After lengthy restoration work, they were exhibited for the first time at the National Museum in late 2011 and early 2012.

Thirty-six photos plus a slide show featuring 466 images from Georges Groslier’s collection were prepared by Mr. Porte, and sent to New York for the forthcoming festival by the National Museum in cooperation with the EFEO.

“This will contribute to the promotion of Khmer culture and the Royal Ballet of Cambodia that was inscribed on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity,” in 2008, National Museum Director Kong Vireak said.

The photos will remain on display at the Lincoln Center until May 11 and will afterwards become part of the archive at the New York library’s Jerome Robbins Dance Division, said Barbara Cohen-Stratyner, the library’s curator of exhibitions. This division is considered the world’s largest and most comprehensive archive on dance.

Georges Groslier would no doubt have approved of his photographs becoming part of this international collection.

As he wrote in 1928, it is crucial to protect classical Khmer dance “to present it with all its vibrancy and regained vitality to those who, caught in today’s times, would have forever deplored its loss.”

© 2013, The Cambodia Daily. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced in print, electronically, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without written permission.