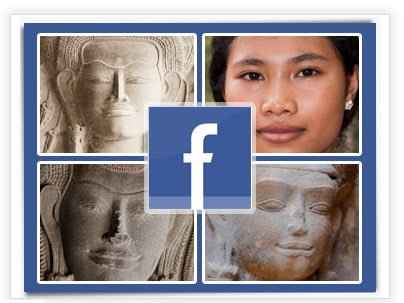

Is Angkor Wat a 12th-century Facebook?

At Angkor Wat: the identities of the mysterious Asian women carved into the 12th century Cambodian temple may finally be revealed.

Andrew Buncombe reports from Asia for the UK Independent

Angkor, Cambodia — Amid the splendour of the 12th-century temple of Angkor Wat, they stand and stare like silent sentinels, sensuous rather than erotic, carved with elegance and care. But exactly who are these 1,796 mysterious women and why, more than a century after Cambodia’s famed Hindu temple was rediscovered by Western archaeologists, did it take the efforts of an amateur researcher from Florida to push experts into trying to resolve the puzzle?

Though Kent Davis had lived in South-east Asia during the 1990s, he did not have an opportunity to see Angkor Wat until 2005. Like most visitors to the huge complex in the centre of the Cambodia, for many years cut off from the outside world because of the presence of the Khmer Rouge, he was mesmerised by the experience.

But he was also left with a flurry of questions. “I went to Angkor as a tourist and I was startled when I got there and saw these women,” said Mr Davis, 54, a publisher and writer who now lives near Tampa, Florida. “I was not prepared for it. The human element of them struck me and I wanted to know who they were. I asked one of the guides and he said they were there to serve the king after he went to heaven.”

Mr Davis’s interest was tweaked, so he wanted to know more. He vowed he would return to the US and investigate. Yet when he got home he found there was essentially nothing written about these women, who appear throughout the temple complex in full body carvings.

Indeed, the only study of the female carvings he could find had been made in the early 20th century by Sappho Marchal, the daughter of Frenchman Henri Marchal, then the curator of the temple site. Frustrated but intrigued, he decided he would find out for himself. Five years and several trips to Angkor later, Mr Davis has slowly begun to get some answers.

In 2008, he asked for the help of computer experts from the University of Michigan. That team was able to conduct facial mapping experiments on digital photographs of the women, or devatas. The team, whose findings were presented last month at the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, an academic convocation in Istanbul, concluded that there were at least eight different facial types, perhaps reflecting a variety of ethnicities in the Khmer kingdom.

The results are to be examined further by archaeologists and more computer mapping is planned. But for all the effort that went into the mapping, the results of which were published in DatAsia magazine, many questions about the women remain unanswered.

“It’s a 12th century Facebook,

but no one has ever heard of this social network.”

“There are almost 1,800 faces there,” said Mr Davis, who now uses 65 separate characteristics to define the individual women in a devata database. “It’s a 12th century Facebook, but no one has ever heard of this social network. This was the biggest temple the Khmer people ever built. It is still the largest religious structure on Earth! It must have been important to them because they threw everything into it. They would have only put their most important images into it; these women must have been incredibly important to the kingdom.”

Mr Davis wrote to universities, pestered experts, and sought the opinions of people from around the globe who had worked at Angkor. Trude Jacobson, an assistant professor of history at the University of Queensland, Australia, and author of Lost Goddesses: Denial of Female Power in Cambodian History, said: “Kent is an enthusiastic researcher of a question that everyone assumed was settled long ago, or doesn’t matter.

“The history of women in Cambodia, until very recently, has been one in which they were relegated to the shadows. His interest is infectious and has made others more interested in questions of gender in an otherwise heavily masculinised historical inquiry.”

What has struck Mr Davis as he has continued his enquiries, is that for all the women at Angkor there are relatively few male carvings.”Could these different women represent the different professions of the Khmer kingdom?” he said. “Could they be scholars, agriculturalists? I think they must represent the most important women in the kingdom.”

Dr Peter Sharrock, an expert on South-east Asia at London’s School of African and Oriental Studies, has studied the temples around Angkor for years. “We understand [the female carvings] little but they play a major role in the architectural sculpture of these temples, which must imply a major role in the beliefs of the ancient Khmers and in the rituals in their temples,” he said.

“Khmer descent was primarily matrilineal, and Khmer women were literate and powerful. Many were queens, and most kings base their genealogies and claims to the throne on their female ancestors. The ancient Khmers venerated the goddess Prajnaparamita in the most elaborate cult to her known anywhere in Asia. So there are fundamental questions here about an exceptional female religious and regal role in ancient Cambodia that remain unanswered.”

Professor Jacobson believes the images were part of a broader iconography relating to the supernatural world. “The devatas, placed either side of doorways, were guards who monitored who was permitted access from the mundane world to the supernatural,” she said.

“[Those] represented as flying or dancing, were responsible for leading the souls of the dead to the supernatural world from the battlefield. The models for the images at Angkor were doubtless members of the royal family.”

Mr Davis said he was dedicated to trying to throw greater light on the mystery of the carvings by working with the team of researchers he has cultivated. At this point, he said, starting to analyse the images was like “being the first person to get a map to the British Museum and the keys to the front door”.

He added: “Once we define facial types more thoroughly, an incredibly exciting prospect appears. If these images are portraits of actual people, it’s logical to assume that they had children within this region, and that creates the possibility of using facial pattern recognition on people living in this area to see if facial shapes and types seen at Angkor still live here. We could actually find the descendants of some of the sacred women in the temple.”

Angkor Wat – Symbol of a nation

- The sprawling temple complex of Angkor Wat, located amid dense jungle and close to the city of Siem Reap, was built in the early 12th century and is one of a series of stunning palaces and temples that were built over a 400-year period by the Khmer Kingdom.

- Today, the temples attract up to a million tourists a year, but for many years the remarkable buildings were unknown to the West, which only “rediscovered” them in the 19th century. During the 1970s and 1980s they were off-limits as a result of the presence of the Khmer Rouge, the Maoist-inspired rebels who ruled Cambodia from 1975-79 and who then engaged in a bitter civil war for the next two decades.

- Angkor Wat itself, the most impressive and best-preserved of the complexes, was built for King Suryavarman II in the early part of the 12th century and is dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu. It has since become a symbol of Cambodia, even appearing on its national flag.