A Record of Cambodia-Cambodia Daily Book Review

A CHINESE COURT OFFICIAL’S

VISIT TO THE KHMER EMPIRE

By Michelle Vachon – The Cambodia Daily

© 2010 The Cambodia Daily –The A Record of Cambodia–Cambodia Daily book review appears with the permission of the copyright holder. No further reproduction is permitted.

Phnom Penh, Cambodia – In 1295, a young Chinese diplomat by the name of Zhou Daguan left the port of Mingzhou in southeast China, bound for Angkor as part of an official Chinese delegation. Little is known of Zhou Daguan — even his name would vary in documents after his death — except for the fact that he took copious notes on life in the Khmer kingdom during his 11 month stay, which were probably kept for an official report but later turned into a book.

Zhou Daguan’s observations of Angkor ended up being the only remaining record on daily life and customs at the Khmer citadel.

As he mentioned in his notes, the Khmer had books: they wrote ordinary texts and official documents with chalk on died-black parchment while Buddhist monks wrote on palm leaves. Those texts, however, have long disappeared, possibly destroyed by humidity, rain and war, while the administrative and religious texts carved on stone at Angkor give no details on ordinary life at the time.

In 1902, the French scholar and Chinese expert Paul Pelliot translated Zhou Daguan’s work into French, and until recently, English-language versions of the book were translations of Mr Pelliot’s French text.

This prompted Peter Harris, a British researcher and international development specialist who studied classical Chinese literature and culture at Oxford University, to translate Zhou Daguan’s book directly from Chinese to English and to publish this new version.

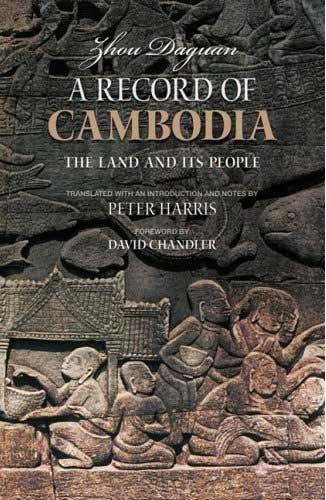

The project; on which Mr Harris casually embarked in the mid-2000’s, became much more complicated than anticipated, he explains in his book released under Zhou Daguan’s original title “A Record of Cambodia, The Land and its People.”

“Putting a 700-year-old book into readable English is not easy to do, especially when the book is written by a subject of one country now very remote from us, about another country about which we understand even less,” he writes.

For instance, Zhou Daguan wrote Khmer words as they sounded to him based on the Chinese pronunciation of his era, Mr Harris says.

“Chinese being a non-alphabetic writing system, its sound system has changed over time without us knowing exactly how;” which adds to the difficulty of identifying foreign words in Chinese texts, he explains.

Identifying monuments and locations described by Zhou Daguan also was no easy task. Beside the fact that the names of temples and places have changed, the Chinese diplomat does not specify whether “stone tower” or “north lake” are actual names of places or just his way of describing them. And since literary Chinese does not have the equivalent of capital letters or other marks for proper nouns, it is virtually impossible to know, Mr. Harris said.

Whenever possible, Mr Harris put in brackets the names of monuments or locations as they are called today, such as Angkor Wat or Terrace of the Elephants.

Mr Harris’ book starts with a chapter on China and the and the southeastern region from which Zhou Daguan came, which puts the Chinese diplomat’s comments on Angkor in the context of his own society and culture, and helps make readers aware of the preconceived ideas and prejudices at may have colored his views.

Originally from a small town near the bustling port city of Wenzhou in southeastern China, Zhou Daguan would have grown up surrounded by, Mr Harris writes, “traders, merchants and sailors, broad-minded outward-looking well-versed in the affairs of the world.”

While Zhou Daguan reveals his appreciation of good living in his descriptions of life at court, festivals and food he appears slightly prudish in his comments on sexuality, which was typical of men of his background.

Still, Zhou Daguan was eager to report anything that might have captivated his countrymen For example he describes at length a Khmer custom he calls “zhentan,” which consisted of having girls (9 years old in wealthy families and 11 in poor ones) deflowered by a monk.

“I have heard that when the time comes, the monk goes into a room with the girl and takes away her virginity with his hand, which he then puts into some wine. […] Some say the monk and the girl have sex together, others say they don’t,” Zhou Daguan wrote.

According to his writing, the Chinese delegation was sent by Emperor Temur Oljeytu Khan to deliver an edict to Khmer King Indravarman III. The diplomats arrived in the Angkorian capital, then called Yasodharapura, in 1296 and returned home in 1297.

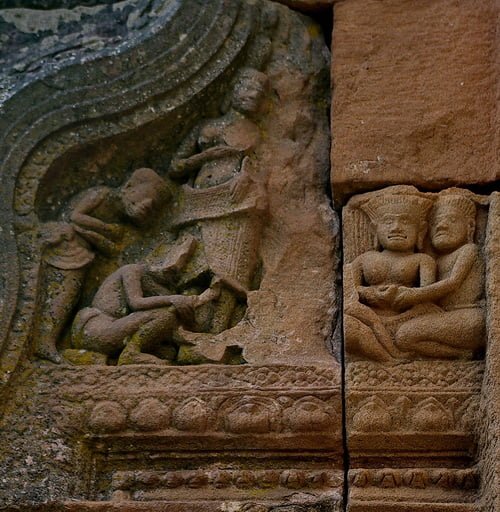

In the Khmer capital, gold was everywhere. In the center of the walled city of Angkor Thorn, Zhou Daguan writes, “is a gold tower [Bayon], flanked by 20 or so stone towers and a hundred or so stone chambers. To the east of it is a golden bridge flanked by two gold lions, one on the left and one on the right. Eight gold Buddhas are laid out in a row at the lowest level of stone chambers.”

He goes on to write about a bronze tower — today’s Baphuon temple; a gold tower in which sleeps the king, now known as Phimeanakas; and a gold tower with a gold lion, a bronze elephant, a bronze cow and a bronze horse, which is now called as Neak Pean temple.

“I suppose all this explains why from the start there have been merchant seamen who speak glowingly about ‘rich, noble Cambodia,’” he wrote.

The young Chinese diplomat described all aspects of life and customs at Angkor, from the New Year celebrations during which the king lighted fireworks and firecrackers, and ways of settling disputes, to health and illnesses, agriculture and trade, flora and fauna, slavery and funerary rites.

Some sections of Zhou Daguan’s book seem incomplete, which actually is the case, says Mr Harris. His text, which was recopied several times over the centuries was greatly cut according to a Chinese book collector of the 17th century, maybe two-thirds of his original text is missing, Mr Harris writes.

“I dream that one day I will stumble across the rest of his text in some obscure corner of the Chinese world, and so produce a much fuller version of his work,” he said in interview.

British by birth, Mr Harris lives in New Zealand’s capital, Wellington. His career has included heading the BBC Chinese Service and representing the organization Oxfam Great Britain in Cambodia in 1981 and 1982. He has also worked for Amnesty International; represented the Ford Foundation in China; and founded the Asian Studies Institute at Victoria University in Wellington.

A fellow at the Center for Strategic Studies in New Zealand, he managed a human rights and justice sector reform project in Cambodia from 2005 to 2007, and is now working in Kazakhstan on a government-civil society policy project.