Armies of Angkor-Siam Society Review by Milton Osborne

The Armies of Angkor: Military Structure and Weaponry of the Khmers by Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h, translated from the French by Michael Smithies.

Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h, Orchid Press, and Michael Smithies as translator of the original French edition, are all to be congratulated for the publication of this book with its intriguing subject. As Jean Boisselier points out in his Preface, the study of narrative bas-reliefs in the temples of Angkor have been of great importance for our understanding of a society that left behind such a limited number of written—or, more correctly, incised—records.

Today, as scholarship has advanced so substantially, it is all too easy, even for a less-than-casual visitor to Angkor, to fail to recognise how much has been deduced from approximately 1,200 inscriptions, many of which have little to do with the material life of the Angkorian period. It is in these circumstances that the importance of narrative bas-reliefs has long been recognised.

Lunet de Lajonquiere, whose fame rests on his having been responsible for mapping temple sites throughout Cambodia in the first two decades of the twentieth century, observed in 1911 that temple bas-reliefs constituted ‘a veritable mine of information’ about Angkorian society and urged scholars to exploit this ‘mine’. This was a challenge partially met by George Groslier, in his “Recherches sur les Cambodgiens, d’apres les textes et les monuments depuis les premiers siecles de notre ere”, published in Paris in 1921. And through his work, and that of others, much information has been assembled about daily life in Cambodia. The bas-reliefs along the outer galleries of the Bayon are, of course, the best-known sources in this regard.

Yet, again quoting Boisselier, surprisingly enough the armies so frequently displayed in these bas-reliefs have not received the attention they deserve, and it is here that our gratitude must go to the present author. In meticulous detail, and sensibly using line drawings rather than photographs for the greater clarity this achieves, he deals with the entire gamut of military aspects associated with the royal armies that existed during the reigns of Suryavarman II and Jayavarman VII and which were depicted on three key temples: Angkor Wat, the Bayon and Banteay Chhmar.

In doing so, Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h sets himself three aims: the selection of bas-reliefs and the study of the weapons used by the different constituents of the army; the study of these constituent parts and their relative importance to each other; and, finally, an examination of the crowds of people surrounding the armies that are depicted. All of this is done against the conclusion that, contrary to the assumptions of various previous commentators, the Khmer armies were not modelled on traditional armies in India.

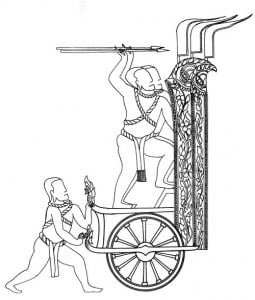

In each of the sections just mentioned the author approaches his task in detail, so that what follows is greatly simplified and should be seen in this light. In terms of weaponry, Jacq-Hergoualc’h makes clear that, with the exception of a limited number of ‘war machines’, for example, a chariot-like mount with defensive shielding used by warriors to launch their spears (figure 29, page 37) or other primitive ‘ballistae’, including ones mounted on elephants, the armaments of the Khmer army were ‘fairly primitive’ and included swords of various types, axes, bows and arrows and spears.

From his examination of the bas-reliefs, the author concludes that the Khmer armies of the period under review were composed of four basic corps: war chariots, cavalry, elephants and the infantry. To this he adds a further classification, allies and mercenaries, while giving separate attention to enemies, and treating the use of boats for warfare as a separate classification. In his detailed examination of these various fighting arms the author comes to a conclusion that would not surprise soldiers of many wars, past and present. Impressive though the cavalry might have been, and intimidating as the elephants surely were, in the end it would seem that the most important role in any battle was that played by the group known for centuries, irreverently, as the ‘poor bloody infantry’.

From his examination of the bas-reliefs, the author concludes that the Khmer armies of the period under review were composed of four basic corps: war chariots, cavalry, elephants and the infantry. To this he adds a further classification, allies and mercenaries, while giving separate attention to enemies, and treating the use of boats for warfare as a separate classification. In his detailed examination of these various fighting arms the author comes to a conclusion that would not surprise soldiers of many wars, past and present. Impressive though the cavalry might have been, and intimidating as the elephants surely were, in the end it would seem that the most important role in any battle was that played by the group known for centuries, irreverently, as the ‘poor bloody infantry’.

As the author puts it, the elephants were ‘so impressive, so numerous, so cumbersome, and possibly so useless’. Images of tanks, incompetently used as they were during the First World War, before their role was rethought by strategists as diverse as Liddell Hart, Charles de Gaulle and Hans Guderian, immediately come to mind. And likewise with his analysis of battles fought on water, the images that he conjures up sit more closely with accounts of Salmis or even Lepanto than any later naval engagements in which armaments and manoeuvrability played a vital role. To the extent the bas-reliefs have a story to tell, it is of the boats of rival armies seeking to join battle alongside each other, with the hope of each boat’s crew that it could board and overcome its opponents.

As the author puts it, the elephants were ‘so impressive, so numerous, so cumbersome, and possibly so useless’. Images of tanks, incompetently used as they were during the First World War, before their role was rethought by strategists as diverse as Liddell Hart, Charles de Gaulle and Hans Guderian, immediately come to mind. And likewise with his analysis of battles fought on water, the images that he conjures up sit more closely with accounts of Salmis or even Lepanto than any later naval engagements in which armaments and manoeuvrability played a vital role. To the extent the bas-reliefs have a story to tell, it is of the boats of rival armies seeking to join battle alongside each other, with the hope of each boat’s crew that it could board and overcome its opponents.

Following his discussion of accessories and camp followers, the author offers a tightly formulated ‘conclusion’ reinforcing his arguments for the paramount importance of the infantry and the uniquely Khmer character of the army. But he does more, for he allows his imagination, soundly based on what he has written and analysed previously, to give us a picture of how he believes the army appeared as it marched off to battle. It is a vision of colour and noise, of a ‘shimmering multitude of parasols, standards and insignia’, of bells and strummed instruments and ‘the booming gong’. As he writes, ‘what a din that must have made!’

Specialist in character though this book undoubtedly is, its appearance will be welcomed by all those for whom a visit to Angkor is more than an occasion for a brief, if wondrous, excursion. The author is to be commended for his contribution to our greater understanding of a society that still remains so elusive in many ways.

Review by Milton Osborne

First English edition, 2007. 200 pp., 4 plans and 154 line drawings, bibliography, index, 24.5 x 17.5 cm., hardcover.

About the Reviewer

Milton OSBORNE is an independent scholar based in Sydney. He is also adjunct professor in the Faculty of Asian Studies at the Australian National University, Canberra, and the author of ten books on the history and politics of Southeast Asia including Phnom Penh: A Cultural History, which is nowavailable on Kindle as an instant download.

Acknowledgement

This review originally appeared in the Journal of the Siam Society, Volume 96. The Siam Society, based in Bangkok since 1904 and under Thai Royal Patronage, promotes knowledge of Thailand and the surrounding region, including many profound works relating to Khmer studies.

Devata.org thanks the reviewer and the the Siam Society for kindly allowing the reproduction of this article in our archive.