From America to Angkor the Artistic Odyssey of Lucille Douglass

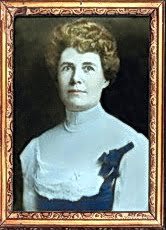

In an era when society expected women to be dainty, passive, and entertaining. Alabama artist Lucille Sinclair Douglass defied conventions by traveling the world and capturing her adventures in exotic etchings, pastels, and watercolors. At the ancient Khmer temple of Angkor Wat, an American artist discovered a special peace that she carried throughout her life…and beyond. “From America to Angkor the Artistic Odyssey of Lucille Douglass” tells her story…

By STEPHEN GOLDFARB, Alabama Heritage Magazine

IN 1926 LUCILLE SINCLAIR DOUGLASS (1878-1935) visited the ancient Cambodian ruins at Angkor for the first time. That December the forty-eight-year-old artist wrote to her friend Leona Caldwell of her first impressions of this far-off and exotic place:

“Angkor is one of the really great experiences of my life-a more intellectual than emotional experience — not that it left me cold, quite the contrary — but it was more of an uplift — an inspiration.

“Our stay — longer than most tourists — was all too short — Angkor Wat alone requires years of study — living with understanding — a few days seems but a mockery.

“I have never had a place affect me so peculiarly. . . . I shall go back for a time as long as I can stand it and do further study on the spot.

“You see the ruins are set in the midst of the jungle — which held them in its clutches for so many centuries that it still seems jealous of them.”

Douglass described the Angkor climate as “the most trying [that] I have ever encountered … [with its] great humidity and high temperatures — an oppressive heaviness which brought all the moisture to the surface [of one’s skin] and left you exhausted with the slightest effort.” And this complaint comes from a woman who grew up in central Alabama.

But Douglass did return the very next year.

She spent five months there with the purpose of rendering the temples and other ruins in etchings, which could capture their grandeur and intricacy in a way that photography could not. These etchings were first exhibited in April 1928 in Washington, D.C., under the auspices of the French ambassador, and then at the French Colonial Exhibition in Paris in 1931. The story of just how Douglass made her way from the Black Belt of Alabama to the jungles of Cambodia is one of equal parts natural talent, hard work, and fortuitous circumstances.

LUCILLE DOUGLASS WAS BORN ON NOVEMBER 4, 1878, in Tuskegee, Alabama, the daughter of Walton Eugene Douglass (a Civil War veteran) and Mary Sinclair (Mollie) Douglass. She grew up in a large house but in the genteel poverty that characterized so much of the nineteenth-century, postbellum South.

LUCILLE DOUGLASS WAS BORN ON NOVEMBER 4, 1878, in Tuskegee, Alabama, the daughter of Walton Eugene Douglass (a Civil War veteran) and Mary Sinclair (Mollie) Douglass. She grew up in a large house but in the genteel poverty that characterized so much of the nineteenth-century, postbellum South.

Little is known about Douglass’s early years, except that she was a sickly child who spent a great deal of time reading, favoring books about travels to distant and exotic lands. In interviews she gave after gaining a measure of fame, Douglass singled out the all-but-forgotten travel stories of Hezekiah Butterworth — whose seventeen volumes of Zig-Zag Journeys enjoyed considerable popularity among young readers near the end of the nineteenth century — as having stimulated her yearning for adventure.

Douglass received her A.B. (baccalaureate degree) in 1895 at the age of seventeen at Alabama Conference Female College, a forerunner of Huntingdon College, where her mother taught. Unfortunately, records do not survive to describe Douglass’s course of study, though it seems safe to assume that she continued to receive art training from her mother, a practice begun when Douglass was a child.

In 1899 Douglass moved to Birmingham, where she made a living as both an artist and an art teacher. She occupied a studio in the old Watts Building between 1901 and 1908. The 1907 city directory listed her as a “china painter.”

Years later Douglass made reference to the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of roses that she painted on teacups and other crockery. The sale of this china, as well as hand-painted place cards, financed her future art training. In 1908 she banded with fellow artists Delia Dryer, Hannah Elliot, Carrie Hill, and four other female artists as founding members of the Birmingham Art Club.

Even before Douglass left for Europe in 1909, she sought art training beyond what was available in Birmingham. For several summers she attended the Art Students League in New York City, though there is no record with whom she studied. Between the years 1909 and 1912, she received art training in Europe.

In Paris she studied with Lucien Simon and René Menard. Of greater importance was the time she spent with Alexander Robinson. With his classes she traveled all over Europe-Holland, Spain, and Italy-and North Africa and became his assistant and an art teacher. After her first year with Robinson, she asked him for a frank evaluation of her work; his reply was indeed frank: “You have less talent than many, but you will go farther than the rest because once you undertake a thing you see it through.”

A collection of her drawings and pastel sketches held in the Birmingham Museum of Art reflect her traditional art training, which emphasized the anatomically correct rendering of the human figure, and depict the local folkways of the places she visited. With two exhibits of her paintings displayed in Paris in 1911, she was on her way to establishing herself as an artist.

By 1913 Douglass had returned from Europe. She spent that summer with artist Isabelle Percy (who married George P. West in 1916), painting in the northern part of Percy’s home state of California.

World War I ended any further hopes of European travel and training and proved a trying time. City directories show that she kept a residence and studio in Birmingham from 1915 to 1917. Some sources claim that she took training as a nurse and worked with soldiers who were “shell shocked,” and that she herself had some kind of mental breakdown, for which she spent time recovering in Texas and California.

Her life took a fresh turn in 1920, when the forty-two-year-old Douglass accepted a position with the Methodist Missionary Society. She was employed to oversee a workshop in Shanghai in which Chinese women hand-colored an early form of photographic slide used by speakers to publicize the missionary work of the society. The job did not absorb all of her time and energy apparently, for she became first a writer and then associate editor of the weekly English-language publication, Shanghai Times, a position she held until 1924. During these years she traveled extensively in China as a member of the press. These trips were often dangerous, as China was in the midst of revolution and civil war.

While in China, Douglass became close friends with two female writers whose books she would eventually illustrate. Florence Wheelock Ayscough was born in Shanghai to missionary parents and educated in New England. She became a scholar of China and its literature, writing books about China and translating the works of early Chinese poets. Four of her books were illustrated by Douglass, the first three with ink drawings and the last with etchings.

The second friend Douglass made in China was Helen Churchill Candee, who had, among other things, the distinction of surviving the 1912 sinking of the HMS Titanic. Roughly two decades apart in age, the two traveled together from November 1926 until January 1927.

This journey led them through the Far East-first to Indochina, then to Siam, and on to Java and BaIi. This adventure resulted in the 1927 publication of Candee’s book, New Journeys In Old Asia, for which Douglass executed twenty-one etchings. It was also on this journey that Douglass first visited Angkor. Candee had been there before and had published the book Angkor the Magnificent in 1924.

Angkor was the seat of the ancient Khmer empire from the ninth to the fifteenth century and was abandoned, only to be rediscovered in the 186Os by French explorers after Cambodia became part of the French overseas empire. Angkor — best known for the two complexes, Angkor Wat and the larger Angkor Thom — was the center of what is considered the most prosperous and sophisticated civilization in the history of Southeast Asia.

Angkor was not only a religious center but also the administrative center of the Khmer empire, with a vast system of reservoirs, canals, and moats-the basis of an extensive irrigation system for agriculture. Eventually the Khmers were overthrown, and the jungle reclaimed Angkor, though the ruins remained a pilgrimage site for Buddhists.

Douglass saw more in Angkor than simply an exotic artistic subject. She gave detailed lectures on Angkor in both the United States and Europe. She also spoke on Angkor at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the School of Oriental Studies at the University of London, the Royal Asiatic Society (also in London), and at Oxford University, as well as many less august bodies. On January 10, 1930, she gave a talk at the National Geographic Society entitled “Angkor — A Royal Passion.” The brochure announcing the lecture gave the following description:

Knowledge of present conditions at the site of the ancient Cambodian metropolis will come to the Society through this interesting speaker, writer and artist, who will illustrate her talk with lantern slides, colored by herself, and motion pictures.

…In company with French archeologists Miss Douglass carefully examined the new excavations…. Her account will be authoritative, as well as entertaining.

For the last years of her life, Douglass made New York her home base, though she traveled frequently to Europe and occasionally visited Birmingham. From November 1928 until late spring of 1929, she was a faculty member of a “floating university.” On the ship President Wilson, Douglass taught art history, sketching, and painting to a hundred “boys and girls” of unspecified age as the ship sailed around the world.

An article in the November 6, 1928, New York Evening Post referred to Douglass as “one of America’s best known painters and etchers” and stated that the ship’s itinerary would include such exotic places as Siam, BaIi, Java, and Singapore, as well as “all the cities … on the more usual type of tour.”

In a letter to her friend, Leona Galdwell, Douglass wrote of her “floating university” experience: “I am glad … to have had the experience, though I should not care to repeat it.”

In a 1933 interview she gave to the New York World Telegram, a fifty-five-year-old Douglass reflected over her life of art and adventure:

I have made my life as I wanted it. I have given up marriage and home ties, because I know they would not be possible with my career. I am sorry not to have a home, but one must not be greedy. I have planned my life just as it is, and I am content with it.

After an illness that lasted several months Douglass died on September 26, 1935, in the home of a friend in Andover, Massachusetts.

Her remains were cremated and, in the following year, flown to Angkor where they were spread around what was described as “a magnificent mango tree.”

Under a spreading mango tree

(Encircling continuity)

There lies for all eternity

What particles survive the flame

Of one who now is but a name.

Civilizations long forgot

Left beauty in old Angkor Vat

An artist loved it well and true:

In paint and print she saved the view.

When she was called, she had one thought:

That was to lie in Angkor Vat.

What doth her Spirit — Who shall say

Where beauty reigns both night and day?

Free as air she is to roam.

With spreading mango tree for home.

Lucille’s Artistic Legacy

In the five years following her death there were three exhibits of Douglass’s works in New York galleries and a fourth after World War II in her adopted hometown of Birmingham.

In January 1951 the Birmingham Historical Society and the Birmingham Art Club sponsored a retrospective of her works at the Birmingham Public Library, which brought pieces owned by museums together with those held by local collectors.

However, very little was written on Douglass over the next half-century, nor was her art exhibited. This was due no doubt to the triumph of abstraction and other modernist movements in art that made the works of Lucille Douglass seem old-fashioned.

Fortunately, there has been a renewed appreciation for her art in recent years, fueled by the current interest in female artists. The publication of Art of the New South: Women Artists of Birmingham, 1890-1950 (Birmingham Historical Society, 2004) by Vicki Leigh Ingham, which devotes an entire chapter to Lucille Douglass, is likely to be the beginning of a revival of interest in this accomplished artist and world traveler.”

About the Author

Stephen J. Goldfarb holds a Ph.D. in the history of science and technology from Case Western Reserve University. In 2007-2008, he curated the exhibit entitled “Howard Cook: Drawings of Alabama” for the Mobile Museum of Art and at the Huntsville Museum of Art.

Goldfarb has written articles previously for Alabama Heritage on artists Marian Acker Macpherson and Lucille Douglass. He now serves Alabama Heritage Quarterly History Magazine as a contributing editor for the “Reading the Southern Past” column. No stranger to Southern reading tastes, Goldfarb retired from the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library in 2003. He has reviewed books for both newspapers and scholarly journals.

© Copyright 2006 University of Alabama – This article previously appeared in Alabama Heritage magazine (Summer 2006, Issue 81) and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the author and the University of Alabama.