Luther College Scholar Paul Cravath Preserves Cambodian Dance History

Paul Cravath, Class of ’66, preserves royal Khmer dance tradition in “Earth in Flower”

by Sara Friedl-Putnam – © 2009 Luther College

This article appears with permission of the copyright holder. No further reproduction is permitted. Download a PDF of this article.

Some 34 years later, Paul Cravath ’66 still remembers nearly every detail of his harrowing escape from the wartorn city of Phnom Penh, Cambodia-including the military flight that carried him to safety.

“Because the airport was under attack from the Khmer Rouge when we arrived, we had to hide in a bunker on the tarmac,” he recalls. “When the rockets finally stopped, we rushed to board a waiting C-130, sinking into the hanging mesh webbing that served as seats as it climbed quickly to avoid ground fire and the wreckage of other planes.”

Cravath would escape with more than his life that day. With him, in the one bag he was permitted to carry, was the research on the all-female Royal Ballet of Cambodia he had spent the previous three months collecting at the request of the Cambodian Ministry of Culture.

Nurtured by Khmer royalty for more than 1,000 years-its dancers unseen beyond the royal household for most of that time-the ballet, with its graceful movements and elaborate costumes, a symbol of the Cambodian people and culture, was considered by many one of the great performing art forms in Asia.

Yet anticipating (correctly) that the Khmer Rouge would try to wipe out the royal dance tradition, the Ministry of Culture had granted Cravath, then a doctoral student in Asian theatre at the University of Hawaii-Mãnoa, unprecedented access to the former royal palace (where the dancers had performed for centuries) as well as the dancers and teachers then with the troupe.

“The official U.S. policy when I arrived in Phnom Penh in January 1975 was that everything was fine even though the city was under siege,” says Cravath, whose research would form the basis of his doctoral dissertation. “It was not a good situation in which to study dance, but I was intrigued by the mystery of these women-what they did and why their reputation was so praiseworthy.”

It would ultimately take Cravath 10 years to complete, but in 1985-after stints teaching theatre at Tulane University, serving as an actor and director with the Hawaii Theatre Festival, and assisting the Tibetan Buddhist lama in Honolulu-he submitted his dissertation and received his doctorate.

Other than a single copy archived at the University of Michigan, however, the work appeared destined, as Cravath puts it, to “live under my bed” until it was discovered in 2005 by Kent Davis, a publisher and Khmer history specialist who happened upon a reference to it in a journal article.

“I immediately recognized the sad historical significance of the information he had gathered,” says Davis, who soon called Cravath to inquire about the thesis and discuss the possibility of publishing it. “More than 90 percent of the royal dancers and teachers had died in the genocide that occurred after Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge.”

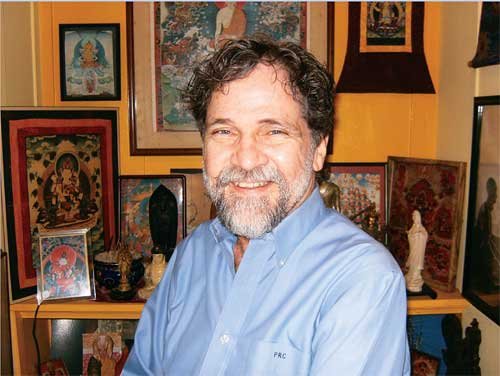

Initially shocked by the phone call, Cravath-a professor of drama at Leeward Community College in Honolulu-was soon spending his off-hours working with Davis to transform his 20-year-old dissertation into a piece polished enough for publication.

“We spent long hours on the phone meticulously talking through every sentence, every punctuation mark until both of us were happy,” he says.

Published in May 2008, Earth in Flower: The Divine Mystery of the Cambodian Dance Drama has received two literary awards, and in January, it was one of three official gifts presented to the King of Cambodia by U.S. Ambassador Carol Rodley. Described by Cravath as “a work of preservation, a descriptive and historical study,” its 680 pages cover the royal Khmer dance tradition from its origins in mythology to modern times.

“I hope Earth in Flower creates a sense for the current and future generations of dancers that this is one of the great art forms of the world,” he says. “I also hope it enhances the prestige of the art form in the eyes of Cambodia and the broader world.”

Though it’s been decades since he fled Phnom Penh, Cravath says his experiences in both Cambodia and Thailand (where he conducted research for several months after leaving Cambodia) continue to inform his work at Leeward Community College, where he teaches acting and directs two plays a year.

He also says that were it not for Luther-and, more specifically, the late Earl Leland, the history professor who successfully recommended him for a Fulbright tutor grant to India-he may never have made it to Asia in the first place.

“I was reborn in New Delhi at the age of 21, and my life for the next couple of decades focused on Asia,” he says. “I’m sure I wouldn’t be where I am today had it not been for Luther.”