Earth in Flower Book Review in Asian Theater Journal

by Toni Shapiro-Phim – © 2009 Asian Theater Journal

This article appears with permission of the copyright holder. No further reproduction is permitted.

Earth in Flower Book Review in Asian Theater Journal

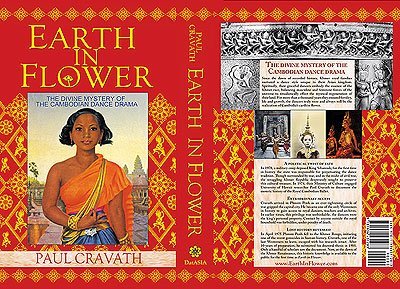

Earth in Flower is a slight revision of Paul Cravath’s 1985 PhD dissertation on the court dance of Cambodia, an art form with a historically intimate connection to the land and its spirits. Except for the addition of some photographs, the publisher notes that he chose to “remain true to Dr. Cravath’s . . . doctoral thesis without modifying, deleting, or rewriting content which reflects attitudes or conventions of use that have changed in the past twenty years” (xxiii).

The book is a treasure trove. It includes more than 180 photographs, drawings, and paintings; listings of early and mid twentieth century Royal Palace performance programs; an extensive bibliography of Chinese, Dutch, English, and French sources, as well as English and French language publications by Khmer writers; and chapters that start with Southeast Asian prehistory and conclude with the dance’s ritual function.

Cravath arrived in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, to undertake research for a degree in theater just as the civil war was tightening its grip on the capital city in early 1975. Before being evacuated to Thailand as Cambodia was about to fall to the communist revolutionaries, he gained access to archival documents, photographs, and artists, some of whom would not survive the following years of deprivation and dislocation.

The Khmer Rouge, under the infamous Pol Pot, took control of the capital in April 1975. By the time that regime was ousted in January 1979, an estimated 80–90 percent of the country’s professional artists (including dancers, musicians, playwrights, and poets), along with close to two million of their compatriots, had perished from starvation and disease or had been executed. Aspects of the cultural knowledge of those who died vanished as well. Therefore this volume presents a unique portrait.

Since 1979, Cambodia’s artistic community has been recreating what it could of the traditional repertoire, with surviving artists painstakingly recalling their embodied wisdom and skills. Performers also continue to develop new works. A resource such as Cravath’s is invaluable in filling in the numerous lacunae in the historic record.

Chapter 1 outlines Cravath’s perspective of Cambodia’s classical dance tradition. Cravath sides with historians who posit a Southeast Asian–centric view of Khmer cultural beliefs and practices, wherein the Khmer are given agency for the creation and continuity of their dance as opposed to the art being viewed as derivative of Indian forms.* Cravath concludes that “[f]or Khmer dance drama, India may have provided a literary medium for mythological expression, and in a much later period the Thai influenced it as well. But in form, in structure, in spirit, and in the selective process operative in its evolution, the dance drama—like the culture in which it flowered—is exclusively a reflection of the Cambodian people” (7).

Chapter 2 examines archeological, sculptural, and epigraphic evidence up to the reign of King Jayavarman II (802–850) in order to establish the long connection of Khmer dance with both temples and monarchs. Chapter 3 focuses on dance during the time of the Angkor Empire (ninth to fifteenth centuries), when Khmer kings ruled over vast parts of mainland Southeast Asia. Sculpted dancing figures grace the numerous stone temples constructed in that era, and evidence points to dramatic performances by dancers associated with royalty.

Chapter 4 takes us from the mid fifteenth century fall of Angkor up to the early 1980s. Codification of Khmer classical dance gestures occurred during the reign of Ang Duong (1848–1860), according to a 1963 publication of the Cambodian Information Department. Cravath notes that Norodom Sihanouk’s first time as king (1941–1955) and then as prince and head of state (1955 until a 1970 coup d’état) saw the dance linked with Cambodia’s nationalist agenda. The dancers, accompanying Sihanouk on travels overseas, came to represent the country to the larger world. Yet, until the 1970s, the special relationship between dance and royalty persisted, as the dancers would perform rituals to connect the people, the land, and the spirits on behalf of the monarchy.

The last part of chapter 4 relies on understandably limited access to information. At the time of the completion of the original dissertation, scholarly, journalistic, and autobiographical accounts of life and art during the rule of the Khmer Rouge and of the first years under the communist regime that followed in the 1980s were few and often contradictory. We now know, for example, that instead of there being “no dancing taking place—folk, classical or yiké—during the Pol Pot era” (178), newly choreographed folk dances performed in peasant/worker garb were an ubiquitous part of Khmer Rouge revolutionary culture. Further, some principal dancers of the previously royal troupe had survived the genocide to perform central roles again in the 1980s and even into the 1990s, belying the author’s statement that by 1975, “The [classical] troupe retained no dancers possessing both outstanding beauty and lead dancer skill” (170).

Chapter 5 looks at various Khmer origin myths and their relationship to the dance. Cravath locates a complementary dualism enacted through Khmer dance—a tension between male and female that is necessary for the wellbeing of the king’s country and subjects and the fertility of the land, in essence, a flowering of the earth.

The next chapters capture crucial information about aspects of the dramatic repertoire as well as about non-narrative dances, and they address musical accompaniment, choreography, staging, training, and costumes. The final chapter explores Khmer dance’s ritual function, with descriptions of the dance as an offering in royal rites. Cravath discusses the buong suong ritual in which, through performance of sacred pieces, dancers beseech deities at the behest of the royalty for blessings for the populace. The chapter also covers the formal sampeah kru ceremony, a salutation to the spirits and teachers of the dance, and the informal rituals dancers may do individually before a performance, as they seek protection and guidance through the offering of incense, candles, fruit, and prayers. The sampeah kru remains central to the lives of Cambodia’s classical dancers today. Since the return of the royalty in 1991, dancers perform at royally sanctioned buong suong ceremonies just as they did prior to the war.

Appendices include a short translation from an early twentieth century French document describing a theater in the Royal Palace; listings of repertoire from selected royal performances between 1931 and 1961; a chart outlining the structure of musical accompaniment, storyline, and timing in a 1971 performance of the Reamker (Cambodian Ramayana); and a list of the pin peat orchestra repertoire as recorded in a late 1960s Royal University of Fine Arts paper. There is a note about the author and a message from the editor about getting this work published.

The dissertation has been circulating among scholars of Southeast Asian performing arts since the late 1980s. Some Cambodian dancers in the United States also have their own treasured copies. Publication in book form invites a broader audience to share in the riches of this tradition’s history and practice and also makes available fine reproductions of photographs, a great improvement over dissertation reprints. The inclusion of additional photographs and an index is also of great value, though some listings of well known individuals discussed in the text are missing or incomplete.

If a second edition of this important book comes, I hope it will contain references to relevant research in archeology, dance, and other aspects of Cambodian culture and history that has been conducted since 1985, as well as to dance scholarship more generally. The University of Hawai‘i has been coordinating an archeological program in conjunction with Cambodia’s Royal University of Fine Arts for more than a decade (see Bong and Stark 2001). In the field of Khmer dance, writings by Blumenthal (1990), Bru-Nut (2002), Sam (1987), Phim and Thompson (1999), and Shapiro-Phim (2002) offer additional perspectives on historical, ethnographic, and ritual aspects of the art and information on artists’ lives and dance technique. Biographies of some individuals whom Cravath mentions appear in recent reference works such as those edited by Brandon (1993), Kennedy (2003), and Leiter (2007). It would also be important to correct copyediting oversights (for example, the name of a prominent twentieth century dancer is spelled three different ways; in the 1980s the country was called the People’s Republic of Kampuchea and this name should be consistently used for that period; photo captions and references to them in the text need occasional corrections).

Nonetheless, this impressive and invaluable study will be of interest to those researching or teaching about theatre, dance, or Southeast Asian history. Readers will need to supplement information with more recent cultural/anthropological, historical, and dance studies that correct errors and shine new light on the context and practice of Khmer arts. The writing is accessible and engaging, and the wide-ranging collection of sources and splendid photographic documentation make it a gift to the field.

Toni Shapiro-Phim

Khmer Arts Academy, Takhmao, Cambodia

NOTE

* The term “Khmer” officially refers to the majority ethnic group of Cambodia. In common English usage (and throughout Earth in Flower), however, “Khmer” and “Cambodian” are generally interchangeable.

REFERENCES

Blumenthal, Eileen. 1990. “The Court Ballet: Cambodia’s Loveliest Jewel.” Cultural Survival Quarterly 14 (3): 35–38.

Bong, Sovath, and Miriam Stark. 2001. “Recent Research on the Emergence of Early Historic States in Cambodia’s Lower Mekong Delta.” Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 21 (5): 85–98.

Brandon, James R., ed. 1993. The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bru-Nut, Suppya. 2002. “Phalla, danseuse sacrée d’Angkor.” In Les Danseuses sacrees d’Angkor, edited by Christophe Loviny, 46–51. Paris: Editions du Seuil/Jazz Editions.

Kennedy, Dennis, ed. 2003. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre and Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leiter, Samuel L., ed. 2007. Encyclopedia of Asian Theatre. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Phim, Toni S., and Ashley Thompson. 1999. Dance in Cambodia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sam, Chan Moly. 1987. Khmer Court Dance: A Comprehensive Study of Movements, Gestures, and Postures as Applied Techniques. Newington, CT: Khmer Studies Institute.

Shapiro Phim, Toni. 2002. “Dance, Music, and the Nature of Terror in Democratic Kampuchea.” In Annihilating Difference: The Anthropology of Genocide, edited by Alexander Hinton, 179–193. Berkeley: University of California Press.