Artistic Visions of Angkor by Maurice Fievet

Artistic Visions of Angkor by Maurice Fievet by Kent Davis

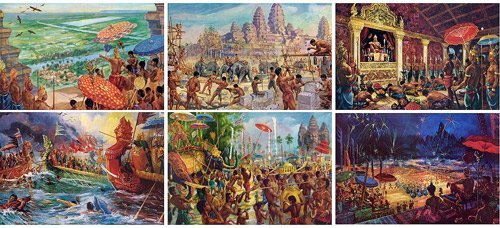

In the 1950s, French artist Maurice Fievet (actually Fiévet – my apologies for leaving out the accent in the title because it is not search engine friendly) — well-known for his work in Africa with his talented photographer wife, Jeannette — created a series of dramatic paintings depicting life in ancient Cambodia.

Fiévet’s paintings were extraordinary because he worked with two of the world’s foremost Khmer scholars — Bernard Philippe Groslier and George Cœdès — to achieve the highest degree of visual and historical accuracy possible.

In researching the life of George Groslier — Bernard Philippe’s father — I encountered photos of Fiévet’s images in the Groslier archive. His paintings finally appeared in the April 1960 issue of National Geographic (Vol 117, No 4.) accompanying Robert Moore’s article “Angkor, Jewel of the Jungle” which begins:

“A many-times visitor to Angkor’s ruins and keen student of Khmer culture, the author links his 35 years of research with remarkable paintings by Maurice Fiévet for an unusual National Geographic article — recreating the daily life of this lost civilization. The talented artist’s drawings underwent minute scrutiny for accuracy by Bernard Groslier and George Cœdès, French scholars who have devoted years to unraveling Angkor’s riddles. The contributions of these talented men, teamed on the following pages, provide a vivid portrait of a vanished people.”

Fievet’s art creates a vivid visual record of the rise, and fall, of the Khmer civilization. The following post shares small images of his important works, with sample quotes from the original 1960 article.

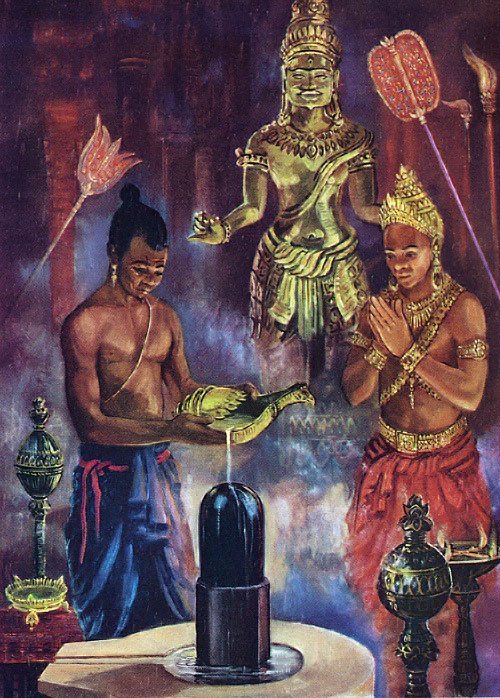

“That there should be in this country one sole sovereign.”

Royal chaplains reported the deification of the kings on a temple tablet now preserved in the National Museum, Bangkok.

Jayavarman II found his country forced to pay tribute to Java. In the year 802 he called upon a Brahman priest “skilled in magic science” to perform a ceremony that would lodge supreme authority in one divine king and declare Kambuja’s independence.

Artist Fiévet portrays the priest anointing the symbol of the Hindu god Siva in rites sanctifying Jayavarman (right) as a devaraja, or god-king, and making it “impossible for this country of the Kambuja to pay allegiance to Java.” For the next six centuries the Khmers dominated Southeast Asia.

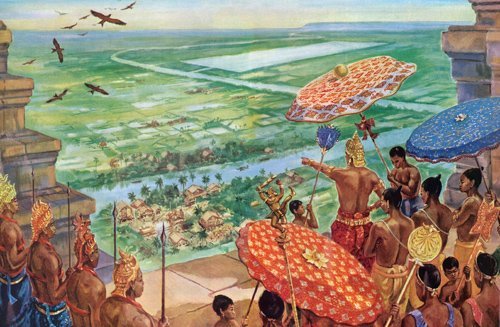

“Then His Majesty… established the royal city.”

A temple inscription details the founding of Angkor, the Khmers’ capital.

One of the first acts of Yasovarman I, the monarch who reigned half a century after Jayavarman II and founded Angkor, was the erection of a “mountain” temple atop a 200-foot hill called Phnom Bakheng. Artist Fiévet portrays the helmeted monarch, surrounded by his spearmen, priests, and umbrella bearers, standing atop the shrine and pointing to the site of the future royal palace. A straightened section of the Siem Reap River forms the eastern moat. The rectangular Eastern Baray, a four-mile-long irrigation reservoir, connects with the river; the king completed it in the first year of his reign. Later monarchs transformed Angkor into one of Asia’s grandest cities, home of perhaps a million people. No trace of their wooden homes remains.

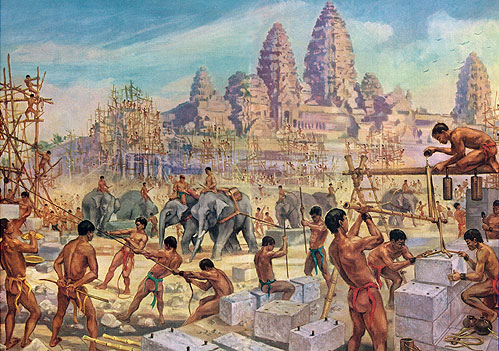

Artist Fiévet, copying details sculptured on the Bayon, depicts a generation’s task. Two laborers in foreground drill holes into which they set pegs for handling. Crew at right slides a block back and forth, grinding surfaces until they fit without mortar ; man atop the frame wets a strap to reduce friction. Gang at left uses rope and pulley to lift a stone. Men on distant scaffolds complete the lower gallery.

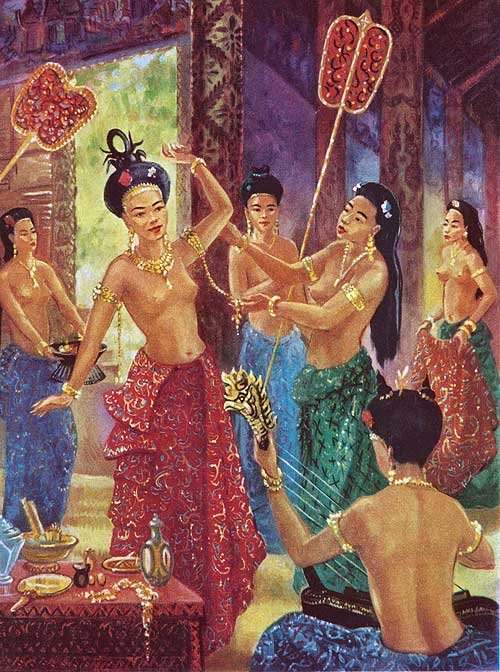

“Sparkling with the fire thrown by the gems of her jewels”

An inscription in the Temple of Ban Theat describes the brilliance of a royal lady.

“In general, the women, as well as the men, wear a bit of cloth about their loins leaving their breasts, white as milk, uncovered,” wrote Zhou Daguan. “They wear the chignon and go barefooted. This is so even of the king’s wives.”

Artist Fiévet, basing his painting on Chinese accounts, temple reliefs, and inscriptions, gives us a peep into the palace as a princess prepares her elaborate toilet. Swaying fans cool her while a harpist entertains. Other attendants adorn her with bracelets, arm bands, and jeweled neckpiece. Vials on her dressing table hold perfumes; bowls contain betel nut for chewing. The hand mirror is a polished bronze reflector. Royal ladies in the Khmer courts became astrologers, Sanskrit scholars, and even jurists.

“Ministers and common people . .. strike the earth with foreheads”

Zhou Daguan, the Chinese traveler, gives us an account of the salaams for a king.

As religious and secular chief, the Khmer monarch judged his subjects’ disputes at hearings twice a day in Angkor Thom. A Brahman priest, identified by topknot and the white cord about his shoulder, presents a petition while standing beneath a parasol, possibly a gift from the king. Other suppliants, who offer baskets of fruit, prostrate themselves.

“The council chamber,” Zhou Daguan wrote, “has golden window frames.”

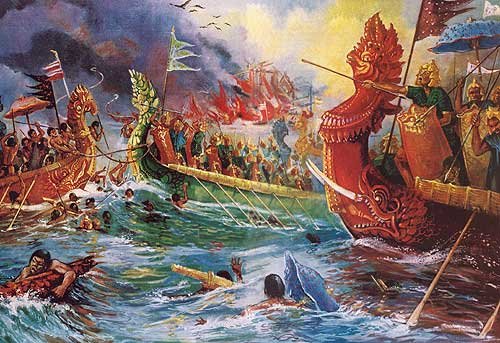

“The King of Champa assailed Kambuja with a strong fleet”

Ma Tuan-lin, a Chinese historian, related the dramatic fall of Angkor in 1177, climax of a 30-year war.

Which the Khmers and which the Chams? Artist Fiévet does not state, as sculptured bas-reliefs on the Bayon show little difference in their dress. Prows of both fleets bear images of the Garuda, a mythical half-man, half-bird sacred to the god Vishnu. As shouting warriors shake shields and brandish spears. one crew casts grappling lines about the enemy’s bow. Survivors from a sunken boat grasp floating debris. Tusk-like projections from the hulls’ painted fish-mouth figureheads appear to serve as battering rams. Screens along the gunwales protect oarsmen.

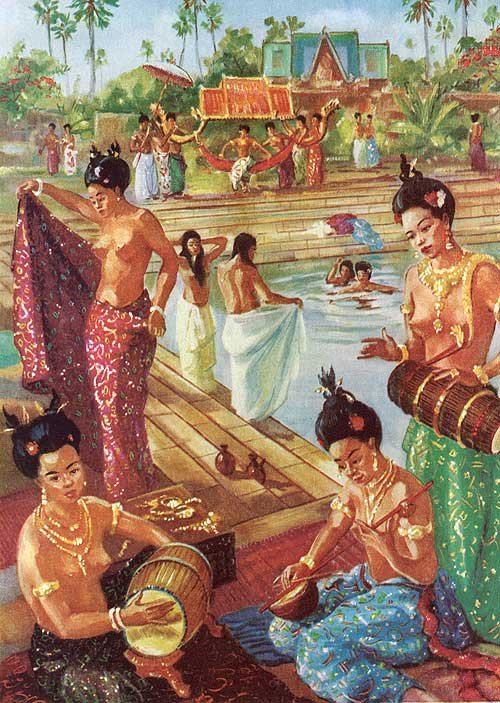

“Among women of the noble houses one finds many as light as jade.”

Zhou Daguan, Chinese traveler

Zhou, who wrote the description above seven centuries ago, reported that

“the king has five wives: one for the private apartment. properly speaking, and four for the four cardinal points. As for concubines and palace girls, I have heard it said that they number 3,000 to 5,000.”

Marco Polo, visiting neighboring Champa in the 1280s, wrote:

“In that kingdom no woman is allowed to marry until the king shall have seen her: if the woman pleases him — then he takes her to wife: if she does not. he gives her a dowry to get her a husband.”

Marching toward one of the city’s four-faced gates. courtiers bear on their shoulders the ark of sacred flame. One attendant carries the royal insigne, a statuette of Vishnu and the Garuda.

Banners, pennants, and mushroom-like parasols dance in the air. The royal elephant wears a golden crown; scarlet brocade veils its companion; gold plate veneers their tusks. Cambodian and Thai courts use similar regalia today.

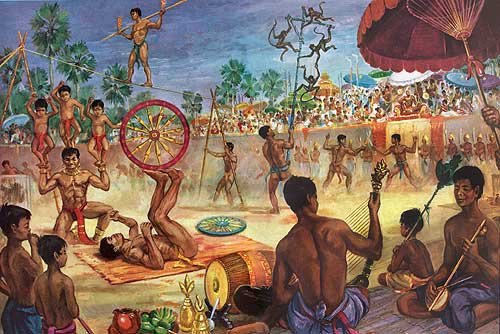

“The King ascends the belvedere to be present at the festival.”

Zhou Daguan

This brilliant circus emerges almost unchanged from wall carvings on the Bayon. The strong man supporting three dwarfs, the juggler spinning a wheel with his feet, and the tight rope walker all suggest the performers in a variety show today. Swordsmen fence, and acrobatic monkeys swing from a pole. A string-and-drum orchestra entertains the king, who sits on the far dais. Pleasure-loving Khmers also matched fighting wild boars, gamecocks, and elephants on the plaza facing the Royal Palace.

“His glory went from himself to the four points of space.”

Queen Indradevi, writing in flawless Sanskrit eulogized her lord, Jayavarman VII

The meditative figure taking shape under this sculptor ‘s chisel portrays Jayavarman VII, Angkor’s mightiest king.

Archeologists have found two of his statues, one at Phimai, in eastern Thailand, and the Angkor treasure shown above. The head of a third image was unearthed recently at a town east of Angkor where Jayavarman appears to have dwelt before becoming a king.

The four faces on the numerous towers and gateways built by the king repeal the statue’s facial characteristics. They represent Lokesvara, a holy one who stayed on earth to do good works, but almost surely are stylized portraits of Jayavarman himself, an ardent Buddhist.

When Jayavarman came to the throne in the year of the “moon, sky, and Vedas” — A.D. 1181 — his queen, Indradevi, wrote: “He rose up to save the land heavy with crimes.”

Angkor’s greatest builder, Jayavarman VII reconstructed the capital. He planned new palaces, pavilions, and the splendid Elephant Terrace that stretches for hundreds of yards along the Royal Plaza; he raised a mighty central temple, the Bayon, second in size only to Angkor Wat.

Nor was the king then content. He built large monastery centers — Preah Khan, Ta Prohm and Banteay Kdei — adjacent to the capital. He erected other shrines and magnified outlying cities. An inscription records that he constructed more than 100 hospitals and erected rest-houses at frequent intervals along the all-season roads he established throughout the kingdom.

Physically powerful, Jayavarman lived well into his 90s, using his years to expand the Khmer Empire to its broadest extent. Jayavarman thus could well say to his people:

“The good works that I have accomplished you should protect, for they are yours also.”

Flanked by nobles and attendants. the monarch sits on a dais and watches his ballet corps weave a magic pattern of color and movement. As the massive Bayon looms against the purple night, banners and pennons flutter beneath exploding fireworks. Chinese, long users of gunpowder, may have taught the Khmers how to mix nitrate, powdered charcoal and sulphur to propel their bamboo-tube rockets.

“Of the qualities acquired, the highest is knowledge.”

A Khmer stone tablet quotes the Code of Manu, the ancient Hindu law book, to emphasize the importance of learning.

Scholars here prepare scripts on sections of palm leaf. Etching the characters with a stylus. they ink the entire strip, wipe the surface clean. and leave the black deposit only in the lettering. Brahman at lower right stacks finished texts for binding with string.

Khmers also wrote on hides, but fire and jungle rot destroyed such fragile books long ago. Only temple inscriptions endure, some written in Khmer, others in Sanskrit, the sacred language of the Brahmans.

“Having drunk the nectar of knowledge,” says one inscription, the king “…gave it to others to drink.”

“The earth is plunged into a sea of ruin wrought by the enemy.”

After 1431 no one left a record of the Thai final conquest of Angkor. Our woeful title is taken from an account of an earlier but less disastrous defeat.

In 1432, a year after the disaster, the Khmers abandoned their capital of Angkor.

***

For Robert Moore’s complete article, “Angkor, Jewel of the Jungle”, please consult the April 1960 issue of National Geographic (Vol 117, No 4.).